|

Herman Brodie is a specialist in behavioral economics, author, international speaker, and founder of Prospecta, a consultancy firm that advises businesses on the use of behavioral sciences research. Many of the hurdles we, or our businesses, face are behavioral. So, over the past 20 years or so, he has helped to find solutions to challenges relating to complex decision making, change management, client relationships, team dynamics, ethics and trust, and has advised hundreds of firms in his primary domain, the financial services industry. This article is a Q&A following a presentation by Herman Brodie at Club b’s family office conference in Monaco. Matthias Knab: Herman, I know that over the last several years you have spent an enormous amount of time with investment teams around the world helping them to optimize their decision processes. What have you seen, and what are your recommendations for teams to optimize their decision process? Herman Brodie: One of the things that has really struck me in my many conversations with investment professionals is how often they speak disparagingly about working in teams. That relates not just to the quality of the decisions those teams make, but also the activities of the team itself, so principally the meeting. This is puzzling because as soon as organizations are faced with a complex decision task, whether it is in investment management, politics, industry or the military, the first thing they do is to put a team together. Matthias Knab: So, teams are like Churchill’s description of democracy: the worst way of government, except from all the others? Herman Brodie: It certainly seemed that way. Why create teams if we are unhappy with them? Philosophers say that frustration like this arises when there is a gap between our expectations and our reality. So, I started my search for an answer there, in people’s expectations. We asked scores of investment managers and analysts what they expected from their group activities. The results made the source of the frustration abundantly clear: none of the most popular expectations occur automatically when people come together in decision-making groups. Matthias Knab: Can you give examples of the most common expectations? Herman Brodie: Sure. People quite reasonably expect more heads to be better than one. The group’s combined knowledge, experience, expertise should be greater than any individual’s. So, group members are collectively expected to provide more information, to be able to correct each other’s errors, and to come up with more ideas. But these things do not always happen. This is because group members have an even more important objective, namely, to simply belong to the group. You see, human beings are intensely social animals. As soon as we come together in a group, we instinctively seek the recognition of other group members. We crave their approval. We want power, status and influence within those groups. We will also seek to avoid being marginalized, sanctioned or to be ejected from those groups. We found that this social imperative really drives everything that is said and done within those groups as well as everything that is not said and not done. Matthias Knab: Do we do this in all our groups? Herman Brodie: To some extent, yes. Sometimes we seek the approval of people we do not even like just to be part of a group. Of course, we are all attached to many different groups simultaneously, like at work, with friends or with family. So, membership of one group might conflict with membership of another, and we must withdraw. But this is not something we do readily. Social scientists describe belonging as a core social motive. Neuropsychologists, like Matthew Lieberman, have done brain scans of people threatened with physical pain (e.g., a punch in the mouth) and those threatened with social pain (e.g., social exclusion), and have discovered that the same area of the brain becomes active. This means that, for the brain, these two threats are indistinguishable one from the other – social pain literally hurts. Yet, the desire to belong was not frequently cited as an expectation among the investment professionals in our sample. Matthias Knab: This means that team members are pursing one thing, to belong, but then expecting another? Herman Brodie: Precisely. But the pursuit of belonging is non-conscious. It constantly gets in the way, but we are unaware of it. As a result, we are frustrated when our efforts at robust decision making are compromised. Matthias Knab: Tell us about the ways this social imperative gets in the way of good decisions. Herman Brodie: Because we want to achieve social status, recognition and approval, we start thinking about it even before opening our mouths in a group situation. How will the information or opinion I am about to share be received by the others? Will they approve? Will I accrue status and influence? Will I be liked? If the answer to these unspoken questions is ‘yes’, then I will be motivated to share. If, on the other hand, I believe my contribution might prove unpopular, controversial, or disruptive, I might think slightly differently about sharing. I might even self-censor. This tendency gives rise to what is known as the Common Knowledge Effect, whereby people in groups tend to spend more time talking about things that everybody already knows – and approves of – than about things that perhaps only one person knows, or that might prove to be controversial. Let’s look at an example of a three-person investment team that must choose between investing in stock A or in stock B. Imagine that each individual has two good reasons for buying stock A, call them arguments #1 and #2, and they all have one good argument for buying stock B, but each a different argument. Collectively, therefore, this team has two arguments for stock A but three for stock B. On the face of it we have a winner, B, but very often it’s A that is chosen. Why? There are three psychological mechanisms that play a role. The first one is simple recall. Remember, each team member has two good arguments for A, and only one good argument for B. If they can remember any argument at all when the meeting starts, it’s more likely to be an argument for stock A because there are twice as many of them. The second mechanism occurs because every team member goes into the meeting with the individual conviction that stock A is the better choice – two arguments versus just one for stock B. If you go around the table and ask what everyone thinks, the group will quickly settle on stock A and wrap up the meeting. This is why you should never ask what people think at the outset of a meeting. The third mechanism results from the dynamics of the group’s conversation. In our example, those dynamics might unfold like this: The first person to speak shares a positive argument for stock A. Not surprisingly, the other two members endorse this argument because they share the same belief. The group then spends some time discussing argument #1 for stock A, even though they all knew it beforehand. Then one of them will mention argument #2 for stock A. Once again, there is a round of endorsements and more time spent in supportive conversation. Now you can imagine the mood is starting to warm, and group members are starting to feel more confident, because they saw their own beliefs reflected in the opinions of other people. Indeed, we can get a dopamine rush when people reflect our ideas and beliefs back at us. At some point, it might occur to one team member that he/she also has a good buying argument for stock B. Against such a backdrop, though, this argument is often withheld because:

As a result, none of the arguments for stock B are ever shared, even though they would have proved decisive. Matthias Knab: You mentioned that asking people what they think at the start of a group meeting is not a good idea. Do you have any other cautionary messages? Herman Brodie: Often decision makers see their job as providing solutions. But this point of view is counterproductive when we work in teams. Team members often adhere to their pre- prepared solutions and are reluctant to change their minds, even in the face of contrary evidence. They then waste time pointlessly defending their original ideas. The goal of a group meeting must be about getting all the relevant knowledge, experience, and expertise out into the open where everybody can see it. Next, they can evaluate it, as a team, and reach a decision. There is almost always some unshared information in groups. This is information that team members have deliberately withheld because it conflicts with their social imperative to belong. If that information is critical to their mission, the team with underperform, while thoroughly enjoying their time together. To encourage the sharing of this unshared information you must be explicit about it, you must say the words. Does anybody have any unshared information? And when people do share this information – which, after all, is what the group wants – they need to be rewarded for it socially. They must be given the recognition, the status, the applause from the boss or from other high-status group members. The ‘social reward’ is incredibly powerful as a motivator, and it is free. Another technique which works well is to assign the informal role of information expert to team members. In these roles, each is responsible for the information pertaining to one key aspect of the decision. For example, as we are talking about stocks A and B, we might make one person the information expert for the firms’ competitive and regulatory environment. We make another person the balance-sheet expert, and the other the expert on the management teams of those two firms. How does one gain social recognition in the role of information expert? One must simply be very good that role. One must be on top of that brief, one must become the go-to person for all relevant information in that domain. Not only are information experts motivated to uncover the information pertinent to their role, they are also motivated to share it in order to demonstrate to others how good they are.

There are numerous other methods organizations can use to encourage more information sharing in their groups. As this is the primary obstacle to robust decision making, I do spend much of my time with investment decision teams working on precisely this issue. Matthias Knab: You say that an investment manager should not be expected a provide answers, just knowledge, experience and expertise. To many, that might sound counter- intuitive; some would say that providing answers is precisely the reason they were hired. Herman Brodie: For complex tasks, intellectual tasks, where there can be no demonstrably correct answer at the moment we must choose a course of action, no individual is likely to have all the answers all the time. Therefore, we create teams in order to increase the pool of resources and to increase the chances of finding the right answers. To take advantage of those resources, we need mechanisms to encourage behaviors like information sharing, and organizational cultures to allow expertise and experience to flow into the decision. Matthias Knab: Allow? Can cultures impede the flow of expertise? Herman Brodie: Absolutely. Imagine an organizational culture where no one dares disagree with the boss for fear of losing his/her job. If your experience and training convince you that the boss’s preferred course of action is wrong then that wisdom will not be part of the decision, at least, not if you want to keep your job. An organizational culture is the sum of all its group norms. These are the unspoken, unwritten rules that dictate conduct and behavior within those groups. So, having the permission to disagree with the boss is an example of a group norm. Group members quickly learn where the group norms are, either by overstepping the boundaries and being punished, or by seeing others do the same. This leads to conformity through self-censorship and to uniformity. Matthias Knab: Where do the norms come from? Herman Brodie: It’s the high-status members of the group who set the norms because they are the ones who have the power to reward and to sanction. Typically, the norm-setters are the leaders. This also means that we cannot talk about norms without also talking about leadership.

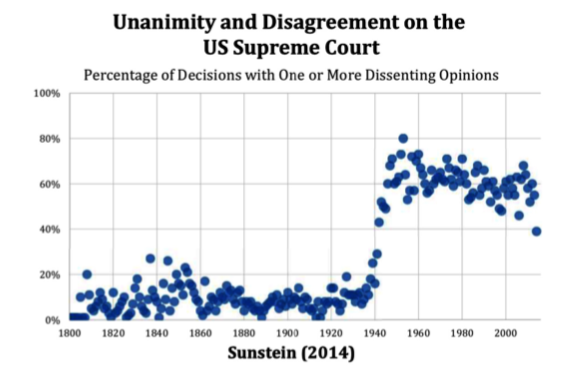

Let me share with you a case study about leadership, and about norms and norm change. On this graphic are 200 years of decisions of the US Supreme Court. Each of those blue dots represent the proportion of judgments each year where there were one or more dissenting votes. In the first 140 years or so, you will notice that dissent was quite rare. In approximately nine decisions in ten, the judgement handed down was unanimous. In fact, it was commonly believed at the time that to have a unanimous opinion gave the judgment of the court more gravitas, so the norm was to strive for consensus. After 1940, though, dissent skyrocketed to about 60% and it has largely stayed there ever since. Why did this happen? One study by Cass Sunstein concluded that this was due to the actions of just one individual, Harlan Fiske Stone, who was promoted from Supreme Court Justice to Chief Justice in 1941 and remained there until his death in 1946. Yet, Chief Justice Stone did not change the existence of dissent on the bench, argued Sunstein, he only changed their willingness to express it. Stone disagreed with the prevailing norm that a consensus opinion necessarily reflected a good decision. He believed that dissent revealed the nuances of the debate and permitted a clearer understanding of the issues for observers. Stone was himself a serial dissenter, so some of those blue dots before 1940 were also due to him. After he became the Chief Justice in 1941, you can imagine that he used his position to promote this viewpoint among the other justices. If they wanted to impress their ‘boss’, an obvious way to do it would be to publicly dissent if they had a dissenting opinion. A second change that Stone made was to give all justices individual responsibility. Until 1941, the opinions of the US Supreme Court were handed down in a single document, called the Opinions of the Court, which was usually written by the Chief Justice himself. If there were some dissenting opinions during the deliberations, the Chief Justice would very likely smooth over those voices in the final text, or just ignore them altogether. Against a backdrop of a consensus-is- good norm, the motivation to share a dissenting opinion would not be very high. Stone changed this practice. Under his leadership, he insisted that each justice write his (there were no women at the Supreme Court in the 1940s) own opinion. That opinion would be etched in black and white for legal scholars to pore over for all eternity. So, they had an interest to write what they genuinely believed. A third change he made was to allow time for longer discussions. If one is facing a complex decision task, and one wants to encourage dissent, discussions are going to last longer. Stone decided that the Court should hear fewer cases (an option that was open to it since 1925, but never used) but discuss them longer in order to air the dissent. I must add that I am not claiming that Supreme Court decisions are better now than they were in the past, although there is a lot of evidence to suggest that groups with dissenters make more robust decisions and are more innovative. The reason I am showing you this case study is that when I speak to investment professionals, they often tell me that the way they make decisions is ‘their way’. It’s comfortable, inevitable, immutable. I want to tell you that every norm feels comfortable, inevitable, immutable. It’s just the shift from one norm to another that’s uncomfortable. Once you get to the new one, it feels just as comfortable as the one that you had before. This means that if you believe that a different norm would suit your decision making purposes better, or suit your organizational goals better, it is possible to change. Look at Stone: he took a norm that had been in place for 140 years, changed it over the space of five and it’s still there 70 years after his death. If he can do that at the US Supreme Court, arguably, the most schooled and experienced group of experts in the country, then, in our humble groups, I am sure that we are also able to achieve it. Matthias Knab: Is it possible to simply abandon this social motive? Herman Brodie: I doubt it. It is an integral part of what makes us human and is the source of other traits, like loyalty, that we find desirable. The solution to improving group activity, therefore, is to organize the decision process in such a way that the attainment to the group’s objectives becomes precisely the route by which one achieves social rewards. This means that when people do the things that the organization wants, they must be rewarded for it socially. This is achieved through recognition and leadership from the high-status members of those groups. | ||||

|

Horizons: Family Office & Investor Magazine

Herman Brodie: The Hidden Motives of Investment Teams |

|

RSS

RSS