|

Since 2012, Anders Meibom has been a full professor in the Institute of Environmental Engineering at the Swiss Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) and is also professor at the University of Lausanne, in the Faculty Geology and Environmental Sciences. His research group focuses on understanding metabolic processes in marine organisms, corals included, under environmental stress. The Red Sea Miracle that could save the world’s coral reefs Over the past three years alone, coral reefs around the world, notably Australia’s Great Barrier Reef and in Hawaii, have seen up to half their living coral damaged or destroyed through mass bleaching. Their prospects for future survival remain dire. Many of the world’s reefs, including 29 UNESCO World Heritage sites from the Pacific to the Caribbean, can expect further annihilation with drastic impact on local economies, such as ocean tourism, before 2050. Anders Meibom, a Danish scientist based in Switzerland’s Federal Polytechnic University in Lausanne has launched a unique cross-border research initiative in the Red Sea involving at least eight different countries that could provide hope for the future of our coral reefs. The effort is based on the stunning discovery in collaboration with colleagues from Israel, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the United States, which showed that the coral reefs in the Northern Red Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba are extremely resistant to the stress of global warming. This is a small miracle against the backdrop of devastation of coral reefs across the planet. In most parts of the world, corals are dying at an incredibly depressing rate. Entire marine ecosystems are disappearing from year to year right before our eyes. As critical sources of marine biodiversity, coral reefs host millions of species. They are also crucial to economic survival, whether as a food source, tourism or protection of coastal areas and disaster risk reduction, for up to 500 million people living in tropical countries worldwide. And yet, this extraordinary natural heritage is in the process of rapidly dying from the effects of global climate change, primarily the steady rising of water temperature caused by increased atmospheric CO2 levels.

Destruction by coral bleaching Take for example the Great Barrier Reef, the Earth’s largest coral reef structure (with a surface area the size of Italy). During the past four or five years alone, upwards of 30 per cent of this immense reef structure has come under direct threat of extinction, or has already died off, as a result of global warming. More precisely, the thermal stress caused by global warming coupled with increasingly frequent heat waves on these fragile organisms cause a disease- like condition known as coral bleaching, which eventually kills these corals. The picture above shows how these bleached corals look – white as snow. What happens is that as waters warm, the coral starts losing its population of millions of little single-cell organisms, small algae, that live in symbiosis inside the coral cells and give the coral its vibrant colors. And while the white, bleached corals may initially have a beauty of their own, they are in fact in a death process. Because corals are at the base of the reef ecosystem, when they die the result is a dramatic decimation of other biodiversity in the reefs, such as the fish population.

The Red Sea Coral Survival Factor Meibom and his collaborators have now discovered (and confirmed through numerous controlled experiments) the presence of at least one region on the planet capable of harboring large and highly biodiverse coral reefs that are much more resistant to the effects of global warming, notably the Red Sea – in particular the Northern Red Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba For the moment, despite the Paris Agreements on curbing CO2 levels coupled with the refusal of many governments to act, it is highly likely that global warming will lift planetary water temperatures by 2-3 degrees C by the end of the century. When this happens, as current indicators and recent extreme weather conditions suggest, all major coral reefs outside the Red Sea are likely to be dead or greatly diminished. If we manage to ensure that the Red Sea corals are properly protected against local environmental stress, then this region could still host a fully functioning coral reef ecosystem. This, in turn, would serve as an immense benefit to the countries harboring reefs off their coasts. These reefs could also serve as an enormous repository of healthy, heat-resistant corals that, with further advances in science, might enable reefs around the world to be renewed.

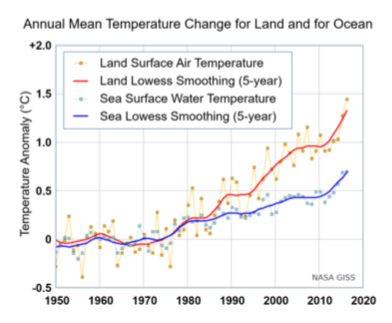

The fact that the Red Sea corals are likely to survive when other reefs are dead, gives scientists a unique opportunity. But, pollution knows no boundaries and effective environmental protection requires international collaboration, coordination and planning. It is for this reason that Meibom’s team, together with the support of scientific colleagues from the Red Sea region, decided to create the Transnational Red Sea Center (TRSC). Significantly backed by Swiss diplomacy, the center is now in the process of pulling together an initiative that will eventually involve at least the eight countries bordering or otherwise linked to the Red Sea (i.e., Jordan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Sudan, Eritrea, Yemen and Djibouti) as part of a long-term ‘cross- border’ scientific collaboration on the Red Sea coral reef ecosystem. The concept of international scientific collaboration is not new, of course. CERN on the outskirts of Geneva has for years been engaged in ‘quiet’ engineering diplomacy on issues ranging from water to nuclear research involving specialists from all over the world, including countries in open conflict with each other. An Unexpected Gift From The Last Ice Age Almost all corals in the world are able to live within a defined and narrow temperature threshold. There is a temperature range they can support or exist in, but when the water gets warmer than that they get stressed and they bleach and eventually die. But in the Gulf of Aqaba, in the northern part of the Red Sea and then the Gulf of Aqaba, the corals there are able to withstand and survive higher temperatures, and it turns out that this is because of a gift of nature which goes back to the last ice age about 20,000 years ago. What typically happens during an ice age is that enormous amounts of water from the ocean evaporate to eventually precipitate as snow and ice around large parts of both the northern and the southern hemisphere. Gigantic glaciers are formed over time. But this also means that the global sea level drops a lot. The last time we had an ice age, the global sea level, all oceans were 120 meters below where they are today. And, as it happens, the opening of the Red Sea towards the Indian Ocean between Yemen and Eritrea has a water depth of only 120 meters. So, when the global oceans dropped, the Red Sea became isolated like a lake as a consequence. But this of course was the kiss of death and ended up killing all life in the Red Sea because of the continuing evaporation of water, the salinity skyrocketed, a bit like the Dead Sea today between Jordan and Israel. When that happened, nothing could survive.

But if we go then a little further forward in time to say 15,000 or 12,000 years ago, we started to get out of the ice age. The melting ice started to raise the sea level of the oceans again, and now fresh seawater was flushed into the Red Sea and renewed the water there. The salinity dropped and organisms began to come back into the Red Sea. The fish migrated back, and the corals were coming back as well, but very slowly because corals are migrating much slower. The main way they move as a population is that an adult colony sends little larvae out that swims a small distance and finds a spot where it forms a new colony. It will then take 10 to 20 years for that colony to become sexually mature and able to form new larvae that may make a new colony another 25 meters down the ‘road’. And so, slowly, also the corals migrated back into the Red Sea from the South after the last ice age. But the waters in the southern Red Sea just by Yemen and Eritrea are some of the hottest waters in our oceans. And so only the corals that could adapt to a very warm water made it through into the Red Sea and then from there migrated further into the Gulf of Aqaba. Today, corals in the Northern Red Sea and Gulf of Aqaba are living in waters are 5-6 degrees cooler compared with the waters the passed through in the Southern Red Sea when they migrated back. But in their biology, they still remember how to live in warmer waters. So, what is happening today as global warming heats up the oceans, in most places the corals die because the temperature is over the limit that they can tolerate. But in the northern Red Sea, in the Gulf of Aqaba, the corals there are able to survive because they still remember the times when they traversed some of the hottest water on the planet. These corals have a much bigger buffer before they bleach and die, and that is really just by chance and a wondrous gift from nature because the Red Sea has this peculiar geological history. Matthias Knab: I would think that you would already have tried to take some Red Sea coral larvae out to the Great Barrier Reef or other dead or dying corals trying to bring the super-powered Red Sea species there so that they may form new colonies there and bring back life Anders: The question if we can transplant the Red Sea corals to other reefs is of course the million- dollar question, and there’s very serious research going on to figure this out right now. At the moment, I think it’s fair to say that the answer is generally ‘not yet’. What happens now is that we can move some species to other places but either they die or they are not happy meaning that they don’t really take root because the conditions are different. For example, the salinity in the Red Sea is higher than the Great Barrier Reef, the microbial fauna is different, the entire ecosystem is different. Corals are very sensitive and not easy to transplant. But with all the progress we have in biology and life science, in for example gene manipulation, who knows what we can do in 10-20 years It might work, but we cannot transplant anything to anywhere if it is dead. This is why at the moment we must do all that we can to make sure we can preserve any coral ecosystem that has come under stress. This is one thing. Another thing is that the global community must by all means work together to protect the Red Sea coral reefs that, because of their unique evolutionary history, are our best change for preserving a large-scale reef ecosystem, because they can tolerate much more global warming.

But the Red Sea corals will only survive if they are protected from local pollution and stress. It’s one thing that they are resistant to global warming, which we probably cannot do much about on short time scales. CO2 keeps going up and global warming is happening – and the temperature goes up, also in the oceans. It seems almost impossible that we don’t hit at least two or three degrees Celsius more at the end of this century, and most other coral reefs will die from that. But the corals from the Red Sea will not. However, as we said, corals are extremely sensitive and they can still be killed by local pollution, and a lack of environmental protection and mismanagement. Protecting those corals is of course a regional task. The reality is that if one of the countries in the Red Sea region is messing it up, they mess it up for everybody. It is therefore very important that we have a transnational effort backed by science and by diplomacy. But the good news is that it is starting to happen and the countries have started to collaborate about something that they all have a shared and strong interest in, both from an ecological and preservation perspective, and because there are also major economic interest at stake here. For example, Egypt has enormous income from their Red Sea tourism. And so, if those corals die, like they are doing it now in the Great Barrier Reef on a really massive scale, it is going to be devastating to the Egyptian economy. A very large number of people are going to lose their jobs and their livelihood. Right now, the coral reefs in the Red Sea are very understudied, we need to know a lot more about them and the entire ecosystem. This is why we organize international and regional collaboration of scientist to find out more about the fragile points and what are their major sources of pollution. We also want to help develop strategic plans and support the decision-making process from politicians and law- makers. We think this is a chance and an opportunity to bring every country from the Red Sea region to the same table, to work towards a shared interest – the preservation of their coral reef. Science is based on international collaboration and the creation and use of synergies, and also here we are dreaming and will hopefully see soon a boat in the Red Sea carrying scientists from different countries working together as an example of collaboration and peacemaking in a region that really needs it.

| ||||

|

Horizons: Family Office & Investor Magazine

The Red Sea Miracle that could save the world’s coral reefs |

|

RSS

RSS