|

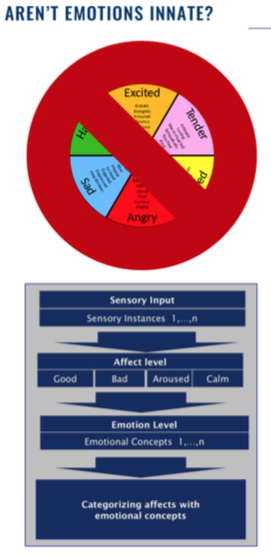

Dominik von Eynern comes from a business family now in the 5th generation and is a Partner of Blu Family Office. He holds a BA in Economics from the University of Augsburg and a Masters in Financial Engineering from the Goethe University in Frankfurt and has over 20 years of experience in principal investment and business development. Behavioral Risks in Successions Matthias Knab: Dominik, in our last conversation we spoke about the role and efficient processes on how to create a family constitution. Today I’d like to talk with you about behavioral risks in successions since I know that this is a theme you have done a lot of research on. Dominik von Eynern: You are right, this is very dear to my heart. Coming from a family business which is now in the 5th generation, we had a couple of successions and just recently in the corporate governance set-up. Families need to accept the fact that every family’s wealth is at risk. There are various risk exposures, far and foremost, behavioral risks, financial risks, and operational risks. When it comes to successions, the usual focus is on solving operational issues, but in my opinion, the focus should be on behavioral risk. The family wealth is usually tightly embedded into and linked to human capital which includes the possibility to deliver and to contribute to the whole as a group by collaboration and cooperation. Now, if behavioral risks strike, the whole human / social capital are eroded, and financial capital loses its anchors and falls literally off the cliff. If you look at statistics, it’s rather interesting that 70% of family wealth transitions fail not because they made the wrong financial decisions. That actually is only responsible for about 5% of all failures, 2% some other reasons. 93% of wealth transitions fail because behavioral risks are materializing, and so, they are, clearly, the biggest risk exposure families have. Wealth succession can be broken down into two parts: Allocation which is basically the question of what is fair, and governance, meaning who is looking after the wealth. Obviously, there’s a relationship between the allocation and fairness and the governance on the allocation side. Theory, where we also try to find out and predict which decisions rational players would make if it came to an allocation problem. The ultimatum game is a very simple game, where you have two possible outcomes. It involves two people, one proposer who is offering a share of his pie of wealth, and one responder who can accept or decline. This is the basic game setup. And now to the rules. When both agree on the split, the proposer gets the remaining share and the responder gets the offered share. And if they can’t agree, all the pie goes to charity. So, the payoff is zero for both. Now, as a purely rational player, you would assume that any offered share above zero is good enough for the responder to say, “Yes, please.” However, in 50% of the cases, offers of under 20% were rejected. So, the responder harmed himself as he didn’t get a payoff because he rejected, and the proposer didn’t get a payoff either, because everything then went to charity. In all those cases, the responder was quite happy to punish the proposer. And this punishment in a family context doesn’t come in money only but also in behavior – reputation risk comes to mind here. When we say fairness is an emotional concept, then we also need to understand what emotions are. One might say that emotions are innate and that we have certain emotions such as happy, excited, scared, angry, etc., but the thing is, these are categories that we have constructed. What we call emotion usually starts with input through our five sensory organs which create a certain level of affect which is undefined at this stage. Their effect can be either good, bad, aroused, calm. And out of those base sensations, we create many emotion concepts. We categorize our sensations into these emotion concepts we can imagine as drawers a general concept; it has a lot to do with social comparison. There might be a hardwired inequity aversion as we saw in the monkey business, or it might also be something like an acquired emotional concept. When we are treated unfairly, we derive negative utility that creates cognitive dissonance, which we are striving to compensate. And when we punish the people who we feel treated us unfairly, we derive positive utility. This is confirmed by neuroscience where it has been found that the reward center of our brains is stimulated when we punish others. Let’s look at what we think is fair. There was an interesting experiment where scientists looked at monkeys to find out if they had a concept of fairness (video link here). The scientists kept monkeys in cages and trained them. They would receive cucumbers in exchange for a stone. The monkeys ended up understanding perfectly that handing over a stone means getting one cucumber. Until one day, one monkey was given grapes which wound-up all the other monkeys. They basically threw out their cucumbers and were complaining, displaying signs of inequity aversion. This study was done by France de Waal. We obviously can’t put humans into cages, and so, we are using methods of Behavioral Game Theory, where we also try to find out and predict which decisions rational players would make if it came to an allocation problem. The ultimatum game is a very simple game, where you have two possible outcomes. It involves two people, one proposer who is offering a share of his pie of wealth, and one responder who can accept or decline. This is the basic game setup. And now to the rules. When both agree on the split, the proposer gets the remaining share and the responder gets the offered share. And if they can’t agree, all the pie goes to charity. So, the payoff is zero for both. Now, as a purely rational player, you would assume that any offered share above zero is good enough for the responder to say, “Yes, please.” However, in 50% of the cases, offers of under 20% were rejected. So, the responder harmed himself as he didn’t get a payoff because he rejected, and the proposer didn’t get a payoff either, because everything then went to charity. In all those cases, the responder was quite happy to punish the proposer. On the other hand, shares between 20% and 50% were mostly accepted as fair. These findings from behavioral science are in stark contrast with what the rational player would do. It’s a bit like monkey business, but surely, we do have to admit we don’t know what fair is. Fair is not a general concept; it has a lot to do with social comparison. There might be a hardwired inequity aversion as we saw in the monkey business, or it might also be something like an acquired emotional concept. When we are treated unfairly, we derive negative utility that creates cognitive dissonance, which we are striving to compensate. And when we punish the people who we feel treated us unfairly, we derive positive utility. This is confirmed by neuroscience where it has been found that the reward center of our brains is stimulated when we punish others. And this punishment in a family context doesn’t come in money only but also in behavior – reputation risk comes to mind here. When we say fairness is an emotional concept, then we also need to understand what emotions are. One might say that emotions are innate and that we have certain emotions such as happy, excited, scared, angry, etc., but the thing is, these are categories that we have constructed. What we call emotion usually starts with input through our five sensory organs which create a certain level of affect which is undefined at this stage. Their effect can be either good, bad, aroused, calm. And out of those base sensations, we create many emotion concepts. We categorize our sensations into these emotion concepts we can imagine as drawers

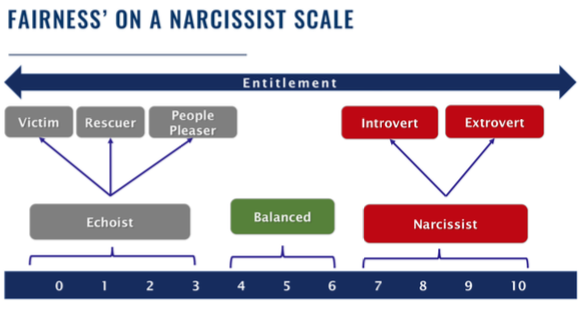

So, we have a sensation, an affect, and then in another step, we try to understand probabilistically into which emotional drawer should I put that affect. Again, it’s probabilistic and in the end driven by our belief system. And sometimes we jump to conclusions, like, for example, the feeling of being treated fair or unfair in a certain situation. But the reality is that what is fair or unfair is a probabilistic approach, driven by our own probability distributions that we learn over life. And as our belief systems and probability distributions are different, people can also have different concepts of fairness. Let’s look at a narcissist’s scale which runs from zero to ten. On the zero end are the ‘Echoists’ who are basically defined as the victims, the rescuers or people pleasers. And on the other, side we’ve got the narcissists – the introverted narcissists who always say, “No one sees me, how good I am, how beautiful I am,” and obviously also the extroverts who can’t be overseen. In any event, the echoist and the narcissists both have a sense of entitlement. You can imagine that in the narcissist’s scale, both these extremes will have different perceptions of fairness. And of course, when we have formed the belief that people treat us unfairly, like the victim, we will look for evidence and tend to only see this evidence. If someone comes with information that would torpedo that evidence and say, “Look, here’s a good example where you have been treated fairly,” we would gladly ignore that. Typically, when beliefs are attacked, we as humans tend to fight. This is what behavioral economists call the confirmation bias because we only look for evidence that supports our beliefs, so, we only see what confirms our beliefs, not what’s happening around us, which is also why the notion of fairness is a complicated one. And, to be precise, fairness or the emotion of fairness is a result of negotiation rather than anything we can throw out there as a notion or a concept as such with a general application.

Let’s turn to governance now. When the principal is handing over the business to the youngster, then obviously, there are mutual expectations. The patriarch expects a positive utility from handing over the business, and that utility is not only driven by money but also by socio-emotional payoffs and the successor is obviously required to deliver that payoff. In any event, the two are in something like a principal agency situation because the patriarch is delegating to the successor, and this situation cannot be entirely remedied by corporate governance since we are speaking of two highly interrelated and associated human beings. But still, how can we mitigate the agency risks I think cooperation is a wonderful thing, but again, what is cooperation Well, in my mind, cooperation is a profitable social exchange and the currency we are dealing herewith are utilities, or utils, of utility functions. So, we have a delivered utility, which must be greater or equal to the expected utility, either in direct reciprocity, which is tit for tat, or indeed, indirect reciprocity, where reputation is a huge influence factor on the propensity to cooperate.

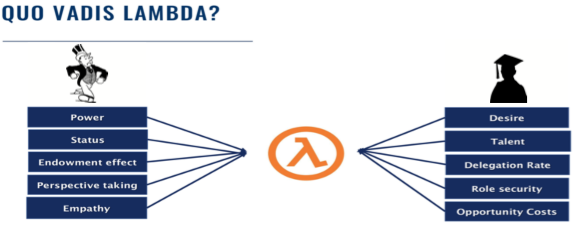

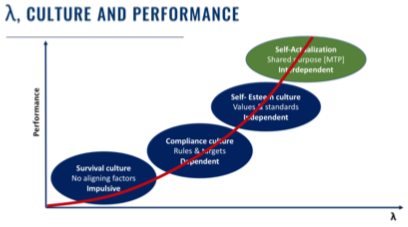

Over many direct and indirect interactions, reputation is built up, and so are expectations. The trouble with expectations is that when we meet expectations, it’s all right; if we over exceed expectations, it makes us happy one time; however, if we undershoot and disappoint, this then has a weight of two. It’s two times worse to disappoint than it’s good to surprise on the positive. Obviously, this dynamic has major implications for the successor and the patriarch/ matriarch succession play. It is therefore extremely important to be clear about the expectations, but sometimes expectations are tacit, which is a problem. Family constitutions are not sufficient to clean that up. To be more technical, we can introduce a cooperation metric called Lambda. When Lambda is minus one, there’s full competition, and when Lambda is a positive one, we have a situation like in a beehive, the perfect cooperation. Now, patriarchs, matriarchs, and successors will be between the two extremes, and each one has more or less an incentive to compete, or to cooperate indeed. So now, the next question is what influences the cooperation factor Lambda On the patriarch-side, he is used to holding the power, which is associated with a status. He loves his status and has a need for status. From that perspective, every inch, every delegation he gives to the successor means he loses status. Like with expectations, losing status is twice as hard as gaining is. This is where his incentive to compete comes from – he wants to maintain his status. Then, he has got an endowment effect, because he worked and built the business for so long, he either founded the business, or he took it over from his father or his mother, and he grew the business, but it’s his business, his baby, and it has been for so many years. And if he doesn’t let go, that obviously comes down to a competing behavior. Another question is his ability to take perspective. Some patriarchs are not very good at taking the perspective of a successor, or even have empathy. Empathizing with the successor is quite a different thing because that means he needs to dial back and see how he behaved in a similar situation back 40 years. And then finally, the successor obviously not only needs the talent, but he also needs to have the desire to join the business. I heard about a family where the successor was trained as an architect and wanted to work as an architect, but father says, “No way that you are working as an architect. You are going to knit socks [or: stay in the family business].” And son says, “No, but I really like to build houses.” He said, “Well then you are not entitled to the business and you are not entitled to the wealth.” So, the son doesn’t even have the illusion of choice. He is forced to work in the business, how does that impact his motivation to work and make it a success challenge is vital to keep trust healthy at an optimal level. We also need to look at delegation in this context. Given the patriarch’s need for power, status and its endowment effect, how much delegation he is really able and happy to give to the successor Often you find a situation where the patriarch says, “Yeah, you do it now, but you know what, you can’t do it this way.” That’s a problem. This also feeds into role security: Who is doing what, and why Role confusion, it is pertaining to conflict. And if the successor really is talented, well, he or she has opportunity costs. They could do something else and maybe something which they enjoy much more and may even make more money. You see, when you define fairness in succession as a result of negotiation, there are many things that are suddenly up for discussion. Let me point out something else here. Sometimes people say that you just need to trust one another and then cooperation works. Yes, trust is very, very important, it’s the most important ingredient for successful cooperation, but there’s a decreasing marginal utility of trust. This means that if you just trust endlessly, the cooperation rate will go down because people who are trusted the most may even have an incentive to misuse this trust and finally end up competing. Again, family and corporate governance help, but the psychological safety to What’s the next challenge then Well, of course, we also need to address who is the successor Is the successor maybe completely overwhelmed with the task at hand Is the successor having some other, especially emotional stress which actually can draw him or her into anxiety or even into depression Very anxious and very depressed people, for whatever reason, are not able to cooperate, to reach out and make it happen. These are all among the things to consider in successions. Think of that architect. He might end up depressed because he’s been actually forced to do something he didn’t want to do in the first place. The fear of social rejection can come into play, or ambiguity, particularly when there is a situation where there are three possible successors and the patriarch just holds back and says, “Well, let’s have a look who might be the one who crystalizes as the most talented.” That ambiguity is even worse than social rejection and causes emotional stress and in extreme cases, toxic stress which negatively impacts the physical well-being. You can see that many behavioral risks can be created on the way to succession which ideally will need to be cleared up before anyone succeeds anyone. The echoist is not able to truly cooperate nor will the narcissist be able to cooperate because obviously he knows it all and he wants to shine in the light. Teamwork is actually impossible for complete extroverted narcissists. We also need to evaluate what kind of performance culture it is in the business. Is it a survivor culture where everything is driven by impulses, where you have no aligning factors People basically, just to make sure they survive until the next year with their very impulsive patriarch and then suddenly the successor does it in a very different way. Or, is it a complete compliance culture Yes, there will be rules and targets, but there you end up with a bunch of dependent people saying ‘yes’. Or, do you have a self-esteem culture with values and standards and more independent thinking which pertains to group intelligence Or, do you have, indeed, self- actualization where you have a shared purpose where people understand they are dependent on one another, which enables the highest form of cooperation. So, how to deal best with succession As I said in the beginning, succession is not only a matter of a family constitution, of legal structures or of tax structures, it is indeed about behavioral engineering.

Succession themes usually involve a few people, but there are strong ripple effects which can go very far. Two individuals are already a group, so there is a need for good and positive group dynamics. If the family doesn’t get on, that would have an impact on the organization and the organization might suffer in performance as a result. That can have ripple effects in communities, in particular when the family business operates in a structurally weak region. And if you aggregate family businesses, it can negatively impact the world - GDP and society. My plea here is to use behavioral engineering to make successions successful. How exactly To my mind, the unstructured needs to be structured and the unstructured is in the heads of the families, of the patriarch, of a successor. The answers are all there, but they need to be brought to light through structured questioning, to find common ground and be clear on mutual expectations. Going through that process make people ‘own’ what was agreed. This is similar to what we discussed in our last interview regarding Family Constitution. People just don’t own what an advisor says to them, but they will usually own what they have worked on and brought up themselves, and that’s the idea behind family coaching. Structure the unstructured by asking structured questions, leading to an outcome that a family really wants. So, the key takeaways are: Successions are at behavioral risk. Fairness is a variable perception and an emotion concept which is created and hence, different for everyone. What is ‘fair’ must be negotiated. Passing on the baton in governance can be very tricky and needs behavioral risk management. Succession planning goes way beyond the tax and legal aspects. I am very happy to speak about these matters with concerned people and share experiences.

| ||||

|

Horizons: Family Office & Investor Magazine

Dominik von Eynern: Behavioral Risks in Successions |

|

RSS

RSS