|

|

Neal Berger Matthias Knab, Opalesque for New Managers.

This article is also available as PDF, download here.

Neal Berger's Contrarian Macro fund was reportedly one of the best performing hedge funds in 2022 with a net return of over 160%.

Neal has been working on Wall Street for over 30 years and has been in the hedge fund industry for over 25 years. He has previously been employed as a Global Macro Trader at New York-based Millennium Partners on two separate occasions. He has allocated capital to hedge funds for over 25 years on behalf of wealthy families and institutions. Neal was previously employed as a Vice President of Proprietary Trading with Chase Manhattan Bank and Fuji Bank in New York. He started his career as a Financial Analyst at Morgan Stanley.

Berger founded Eagle's View Capital in 2005 and launched a hedge fund of funds in June 2010 with the aim to provide investors access to a range of niche hedge fund strategies and markets that are often overlooked by most traditional and hedge fund investment vehicles. According to an investor documentation reviewed by Opalesque, this fund has since inception in June 2010 vastly outperformed (cumulative return of 161.41% versus 48.77% for the HFRI FOF Composite Index and annualized Sharpe Ratio of 1.45 versus 0.54 for the index.)

In this new "Opalesque 1:1" series, however, we will be looking beyond numbers and ratios, trying to understand the person and what shaped the manager's investment style.

Matthias Knab: Neal, the Contrarian Macro fund which you set up in 2021 was reportedly one of the best performing hedge funds in 2022 with a net return of over 160%. I would believe that the substantial global media coverage got people interested in you personally as the manager and the brain behind the strategy. Your career spans over three decades on Wall Street. Let's go back to 1989 which was the year that the AT&T Collegiate Investment Challenge came out. You decided to participate and promptly ended up ranked #9 out of over 25,000 college students from around the country competing in that competition.

That's already a stunning start, please tell us more how and when everything began?

Neal Berger: You know, my father's two passions in life are investing and sports, although he was a pharmacist, so he really wasn't in the investment business or the sports industry. But what's interesting here is that my brother went into the sports field, and I went into the investing field. It looks like there was something that rubbed off from my dad's interests.

Then, let's not forget that the movie "Wall Street" came out in 1987, right around the time when I entered college. I didn't aspire to be a bad guy like Bud Fox or Gordon Gekko, but it was an exciting movie and I learned about Wall Street from it. I think that movie is still the greatest movie ever done about Wall Street. So that piqued my interest in the field, and the only thing I knew about Wall Street at the time was that people called "stockbrokers" were working there. So, when I thought of Wall Street, I thought of a stockbroker.

I remember back in high school thinking, "what am I going to do with my life?" and looking at the list of highest paying careers, which was one criterion of course, "Let's see where I can make a lot of money." Today, I would advise people to go into what they love. In my case, I just happened to love what also was a lucrative career - if you can get into it. I'll talk about that in a moment.

In high school, most people don't really know what they want to do in life. To get some ideas, I looked up careers that pay a lot of money and I found professions such as doctors, lawyers, and accountants. But at the top of that list, at least back in the '80s, was stockbroker. I think the average annual salary for a stockbroker was around $250,000, and the average annual salary for a doctor was like $150,000 or so.

As I mentioned, I didn't know a lot about Wall Street and that there were careers other than being a stockbroker. Of course, I didn't become a stockbroker right away, but I was determined to get there. Soon, I got my first job. It wasn't an internship, but let me tell you how it started.

Back in the 80s, when people still used to go to shopping malls, I met these two guys that were sitting in the mall near where I lived who were trying to attract clients for their brokerage firm. They had a little booth set up and the firm was called Thomson McKinnon. I don't think it's around anymore. I approached them and said, "Do you have any job openings?" I was going to be home for winter break, and they said they would hire me for the week to be a cold caller. I don't think I really knew what that was, but I was looking for a job and it sounded good, and I felt like I was working with a "Wall Street" firm. So I worked that week with them as a cold caller, which is essentially calling people who don't want to talk to you, trying to convince them why they should buy stocks from the firm I was working for. But it was a lot of fun. There were a lot of young people working in the office and a lot of laughs, and a lot of good times. It was a fun environment, so, I enjoyed that.

Matthias Knab: How old were you then?

Neal Berger: I must have been 18. So, I learned what being a cold caller was and I worked in the atmosphere of a local stock brokerage firm, although at that time, I thought this was big time Wall Street, even though Thomson McKinnon was in Nanuet, New York. The following summer, I ended up working for Shearson Lehman in Paramus, New Jersey.

Matthias Knab: How did you get that job?

Neal Berger: Like a lot of kids, I sent out letters. There was no email back then, so you had to send out physical letters to lots of different places looking for summer jobs. Most of the rejections that I got were form letters. But one of the letters sounded like it was somewhat personalized.

I remember the letter said something like, please contact me when you graduate from college or something along those lines, so I thought maybe it wasn't a form letter and therefore I ended up following up and calling the person anyway just to say thank you for the letter and really try to convince them to hire me. As it turns out, those are the qualities that one needs to be a good stockbroker, a good salesperson, and not taking no for an answer.

Matthias Knab: Tenacity.

Neal Berger: Exactly. So, I think that impressed the person who had sent me the letter, a branch manager of Shearson Lehman in Paramus. His name was Irwin Dublirer. I think he's still around, but today I believe he was impressed that I had gotten a rejection letter from him, but still followed up and didn't take no for an answer. So, he invited me to come in under the pretense of simply having a chat. Of course, I was very enthusiastic to do that, because I looked at him as a major Wall Street player. Remember, at that time, I didn't know all the different hierarchies in the business. I mean, he was a local big shot, the branch manager of an office of Shearson Lehman, which was a major Wall Street firm. And so, I went in and talked to him, and we ended up sitting for about two hours and I think he was impressed. I must have presented myself well as I was very enthusiastic, young, and full of energy.

Matthias Knab: Neal, even 30 years later, I see you full of energy and focus every time I speak to you!

Neal Berger: Yes! This business is my avocation in addition to my occupation. I am just as passionate about it today as I've ever been. I'd do this job for free but don't let that get out too far...

Back to Irwin Dublirer of Shearson, by the time our conversation ended, he called in one of his top brokers and he said, "You're going to hire this kid for the summer to do cold calling for you." Obviously, I was thrilled. He paid me $400 a week, which was a tremendous amount of money at that time. My jobs prior to that had been working at Burger King and A&P Supermarket. I remember my starting wage at Burger King was $3.35 an hour which was the minimum wage at the time. When I moved to A&P, I got $3.85 an hour. I did well and had gotten raises, so I topped out at $5.05 an hour. When Shearson Lehman hired me, it was for what felt like a tremendous amount of money, and I would be working at a Wall Street firm. I felt like I had really made it. This was the year between freshman and sophomore years in college.

Matthias Knab: When did the AT&T Collegiate Investment Challenge where you finished ranked 9th come into play? Did you have any formal investment or trading education by then?

Neal Berger: That competition wasn't until the senior year of college, and by that time I had already worked for Shearson Lehman, Bankers Trust, and JP Morgan in various internships.

I finished the Shearson Lehman job during the summer between my freshman and sophomore years. And it was great, it was a lot of fun. Lots of young people, we were playing softball, going to bars, having drinks after work. It was really a wonderful atmosphere because all these guys and gals were in their mid-20s while I was 19. So I was hanging out with young people who all seemed to have some money. Unlike my college friends where we would go for 5c chicken wings and $5 pitchers of beer, these people had a little bit of money. That meant we were going to restaurants one step up and could order anything we wanted, which was new to me. I had always been the guy who had not more than $10 in my pocket, and I had to make it last.

Of course, all of this got me even more interested in Wall Street. I went back to school, and I worked at a supermarket again, Price Chopper in Albany, New York to make a few dollars. My parents asked me to pay for half of my college. They could afford the full thing, but they wanted me to take some accountability and pay for half of it, and I did. I worked as a cashier and then, of course, I wanted a little bit of going out money, so I worked.

The following summer between my sophomore and junior year, I learned about other careers that were available on Wall Street.

It wasn't just being a stockbroker; there was something called investment banking, there was something called trading. I was fortunate to get a job at Bankers Trust in the real estate finance group, which was on the investment banking side. This was not on the trading side, so it was much more deal oriented. I worked for a woman named Debbie Harman who was the youngest managing director ever at Bankers Trust, I believe she was 29 years old at the time. This group was heavily involved in making loans to the large real estate developers in New York, such as Zeckendorf, Tishman, Milstein, and Donald Trump. So, I got to meet a lot of those people. This was big business and a big deal. Bankers Trust was New York, 280 Park Avenue if I remember correctly. Working there, I saw another side of the business, working on the investment banking side and I also enjoyed that summer. We didn't have a softball team, and they weren't going out having a beer after work - maybe they were, but they weren't inviting me in any case - but it was much more serious, real New York Wall Street, but on the investment banking side rather than the trading side.

Debbie Harman had a lot of relationships and influence within the bank, so she made some calls because she could see that my interest was more oriented toward trading rather than investment banking. She was so kind to make a few calls down to the Bankers Trust trading desk and got me opportunities to sit with some of the traders, which, again, was a real New York City Wall Street trading environment. It wasn't a local brokerage firm any longer. It was the big leagues. I didn't work on the trading desk that summer, but I was able to sit with some of the traders and see the real transactions going on the syndicate side and on the trading side and all that.

By that point, I had decided that Wall Street was the business that I wanted to go into. The following summer, between junior and senior years, I worked at JP Morgan as an intern. I was able to work on the trading desk, on the syndicate desk. That was when I really decided that trading was the side of the business that I wanted to go into. I felt like this was my home.

Matthias Knab: Neal, coming back to the AT&T Investment Challenge, did you have real trading experience when you entered the competition? How did you manage to end up on rank 9? During the competition, your best weekly ranking was fourth at one point, which probably also made you a hero at your college.

A young Berger featured in Albany Student Press in 1989.

Neal Berger: That's an interesting question because when I entered the competition, I had never really traded. I didn't have a brokerage account, but I had learned that this is what I wanted to go into.

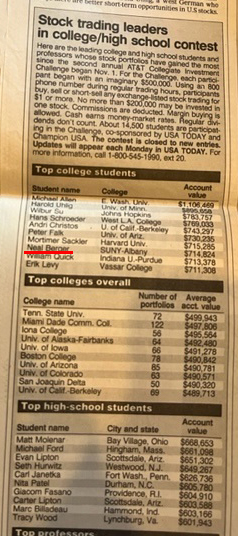

As you mentioned, in my senior year the AT&T Collegiate Investment Challenge came out. More than 25,000 college students from around the country were competing in that competition, and they gave you a $500,000 fictitious account. There was a trading desk number that you had to call to make trades. It was run very well and then they would publish the top 10 leaders every Monday in the USA Today newspaper. I think the contest ran for about three months, trying to turn $500,000 into as much as you could and USA Today would publish the top 10 in the country.

I was steadily up there on the leaderboard throughout most of the competition. As I said, this was all before the internet, so you can imagine how exciting it was to go and check the newspaper to learn how I and the others were doing.

Matthias Knab: Do you recall your investment process at that time?

Neal Berger: Yes sure, I remember the methodology I used to trade. Looking back on it, I do remember my thought process, it was quite simple. My first assumption was that I'm not going to win this competition by turning $500,000 into $550,000, with a mere 10% gain. I had to be much more aggressive in the way that I did the trading because this was not a competition over a long period of time. This was trying to make as much money as possible within a very short period. So buying something like IBM, which was the bellwether blue chip stock, wasn't going to win me the competition. I realized I had to buy more volatile stocks that had the potential to move very sharply, hopefully in my favor, to win the competition. We also had certain rules. You couldn't put all the money into one stock. I think the maximum you could put into one stock was either 10% or 20%; they were trying to avoid somebody buying one stock and having it go up and winning the competition. So it was designed very thoughtfully.

I remember my thesis was that I had to buy stocks that have the potential to move quite a bit. I think that was smart, because looking back on it today, if I were trying to win a competition for a three-month period, I would use the same approach today.

I also remember looking at the Wall Street Journal, because that was the way we got our information back then. There was nothing online. I combed through all the various stocks and looked at the range between the high and the low for numerous stocks. I was looking for large ranges between the 52-week high and low. Stocks that had, for example, a low of $2 and a high of $20 during that 52-week period were interesting to me. I was looking for volatile stocks that had the potential to move substantially. Let's say the 52-week range was $2 to $20 in a particular stock, my second criteria were that the stock was trading at the very low end of that range. A perfect stock had a 52-week range between $2 and $20, and it was trading at $2.20 or $2.50. I think there was another rule, a maximum dollar amount per trade. So, let's say if 10% or $50,000 was my max, the contest allowed you to buy $50,000 of a $2 stock which buys you a lot of shares as opposed to $50,000 of an expensive stock. So, I figured out how to game the competition as best as I could, because if you're buying a stock that trades for $150 with a maximum spend of $50,000, the number of shares that you can buy is much lower than if you're buying $50,000 of a $2 stock. Obviously, you could buy 25,000 shares of that. So, I did that, and it worked, and my $2 stocks went to $4. And then maybe I'd watch the ticker every now and then, and if I thought it might be topping, I sold out. There was obviously a lot of luck and randomness to it as well, but you could also argue that it was a purely quantitative strategy. I didn't even know the names of these companies, nor did I do any fundamental research or anything like that.

Looking back on it now as a professional trader for many years, it was the right methodology, because the fundamentals don't really play into it that much if you're playing for the next three months, which is what the competition was about. It didn't really matter what the long-term earnings of the company were going to be when your horizon is only three months maximum. I wasn't investing for 10 years, I was investing to win a competition for a three-month period. I stuck to my guns and executed what I thought was the right methodology, and with a little luck, it turned out that I picked some good stocks and ended up coming in 9th in the country, which was a big deal.

One of the weekly leaderboard tables in USA Today.

Matthias Knab: Did that help you going forward, like in getting the next job?

Neal Berger: The next job I got was my first real job when I was recruited out of college by Morgan Stanley. I went to a state school, SUNY Albany. The campus wasn't inundated with the biggest Wall Street firms in the world that were looking to recruit. This wasn't Harvard, Wharton, or another Ivy League university. It was SUNY Albany, which was a great school at the time but at the end of the day, it was a state school. And so, there were only a few companies in the category of let's say a Morgan Stanley that came to recruit at the school. At that time, SUNY Albany was known for accounting, so all the major accounting firms, I think it was the Big Eight or whatever it was back then, were recruiting at the school.

I wasn't much interested in accounting, although I had done well. To me, Morgan Stanley was the best company that had come to recruit at school. I went for that interview along with so many other people who desired to work at Morgan Stanley who graduated that year, which was about 4,000 people. As you can imagine, there was a lot of competition even just to get the interview. Back to your question, was the college trading competition helpful then? I think so. When a recruiter who's doing on-campus recruiting sees that you have been with Shearson Lehman, Bankers Trust, and JP Morgan, and are a top 10 performer in AT&T Collegiate Investment Challenge and compares that to other college students in deciding who's going to get a second interview, I think it was helpful to have that experience in addition to the internships that I had done. It obviously showed that I had some aptitude and some interest in Wall Street, which I think was good enough to differentiate me, to be selected as maybe 1 out of 25 or 50 people that got an on-campus first-round interview with Morgan Stanley to be a financial analyst.

I did very well apparently in that interview. I remember that I studied quite intensely for the interview, learning about all the different deals that Morgan Stanley had done and asking the recruiter lots of questions that looking back on it, certainly the recruiter had no idea about. My questions were probably much different than some of my peers who were asking "how much vacation time do you get?" or "what are the hours like?" and that sort of thing. I was asking real penetrating questions and I think the interviewers, looking back on it today, they were probably kids in their mid-20s that were like, "Who is this guy that knows all these questions to ask?" And they didn't know the answers, of course. They were just, "Well, that's a really good question, and we'll have to come back to you with the answer."

But what I think I left them with is that I had done my homework and that I really wanted to work on Wall Street, that I really wanted to work for Morgan Stanley and I was willing to put in the time and the energy to do that research and learn a lot about the company, its prior deals, and ask intelligent questions versus just looking at the interview as a generic exercise.

Here is another thing. I majored in economics, but I did a double minor in business and Japanese language because at the time when I was graduating college, Japan was going to take over the world. The 10 largest banks in the world were Japanese, and Japan was very dominant in the economic landscape then. And so, also to differentiate myself from other economics majors, I minored in the Japanese language. Of course, I can't speak it today, but I think that was also a bit of a differentiating factor.

I even got a job in something called the JET Program, The Japan Exchange and Teaching Program. So, if I didn't get the job on Wall Street or at Morgan Stanley or somewhere else, I had planned to go to Japan and teach English and become completely fluent in Japanese. I think that was a two-year program. I had planned to go live there, teach English, and come back to the US and maybe try to get a job on Wall Street, being fluent in Japanese, which I thought was an edge over other just generic economics majors. But I was very fortunate and was one of the few selected by Morgan Stanley to have a second interview in New York City at the Morgan Stanley offices. I had never dreamed I would get that far, quite frankly.

Again, I did a lot of intense studying and research even more for that second interview, and I guess they thought enough of me to hire me. I remember there were two kids that were hired out of my class at SUNY Albany - myself and a girl named Holly Bornstein, who was the president of the student body at that time. As you would guess, Morgan Stanley was obviously very selective as to who they hired, and it was a big honor to get hired. Every single other person except for myself and Holly in that analyst program had graduated from an Ivy League school while we were the only two that were from a state university.

Much to their dismay, I told the people at the JET Program that I was not going to be traveling to Japan. My parents were very happy because they didn't want me to go to Japan, but I was able to get the job at Morgan Stanley and that really launched my Wall Street career at that point.

Matthias Knab: That's extremely interesting to hear your story about your early days. How has your style of trading evolved through all these years?

Neal Berger: It's hard to say. Let's start examining this by going back to Morgan Stanley. Remember that I started as an analyst, I wasn't trading then. About 10 months into my role as an analyst, I recognized that I really wanted to be a trader. As an analyst, I was supporting, working, with the international equities desk at Morgan Stanley, and so I just kept asking them, "Hey, are there any jobs for me?" Even though I was an analyst, my heart was much more into the days of the yelling and screaming in two phones and this very exciting type of environment rather than having to go back to my little cubby hole and do analysis and things like that. I wanted to be rocking and rolling on the trading desk instead.

An opportunity came along for me to get a job at Fuji Bank, which was one of the largest banks in the world at the time, now part of the Mizuho Group. At that time, I was very lucky to get placed into a proprietary trading group. It was a group that simply put the bank's money at risk in the US interest rate curve. I was trading the short end of the US yield curve, there was an entire group dedicated to just proprietary trading within the short end of the US yield curve, Eurodollar futures, and short-term swaps. It was a time when the Fed was easing aggressively. I think the Fed funds rate had been 9% and ultimately came down to 3% during my tenure at Fuji Bank. At that time, it seemed incredible that interest rates could be 3% on an overnight basis, that really seemed incredibly low.

Fuji Bank was a great place to work. Japan has this concept of lifetime employment. Once you get a job at a Japanese firm or a Japanese bank, they don't fire you, though they may reposition you in other departments within the bank. It was a very different type of style whereby once you're working there, you're part of the family. You're expected not to quit, and you're expected to essentially work there for your entire career. Now, they didn't expect that of me as an American, they knew that I had a different culture. They always expected that it would be a bit of a stepping stone for me, they understood that. I think that they hired me because I was coming out of Morgan Stanley. Morgan Stanley and Goldman were the two premier names on Wall Street at the time. Also, I did have the minor in Japanese language, so I understood the culture. I understood the language. Even though they spoke English very well, we were meeting with a lot of senior economists on the street and influential people, and I think that they wanted to have someone who could help them bridge the gap. Maybe they misunderstood some nuances of what somebody was saying and that I could translate that from English into Japanese for them so that they could fully grasp the nuances associated with it.

Fuji gave me a great opportunity to trade and learn from the markets. There's no college class that can teach you how to trade. Even if you're sitting with a mentor, everybody must develop their own style. It's akin to being a painter. You can go to a painting class, or you can watch somebody else paint, but it must come from you, and you have to develop your own style. Any good trader would say, risk management is an extremely important part of being a trader, trading with the major trends and not trying to fight the market is also important. Where the rubber meets the road is the question, what do you consider a major trend? Because somebody could look at the last two weeks and think that's the trend, and then somebody could broaden out and say, "Well, no, if you look at the last six months, the trend is down." And even though the last two weeks, the trend has been up. I personally am looking more at the last six months or the last year or so.

Therefore, the trend is always in the context of the timeframe are you looking at. If you're looking at the past 100 years as your timeframe, well, the trend in stocks is always up. When you talk about trading with the trend, you're implying that there's some timeframe that you're looking at to determine when that trend starts. Some people trade based upon a two-minute trend or three-minute trend, or whatever it is. You must determine your target zone when you're looking at a trend in terms of the timeframe.

Risk management is very important and that was something that I probably learned most at Millennium working for Izzy Englander. Izzy and Millennium are famous for their incredibly good risk management. And so, I really honed that at Millennium Partners.

I would say that there is something that I have brought to the table on my own. When people talk about trading, the adage is cut your losses quickly. And yes, that's important. But I would say equally important is that when you have the best of it and when you are in sync with the market and you're winning, you better be super aggressive. You better have the courage of your convictions to really take advantage of those opportunities in an aggressive way. Yes, it's important to be wimpy and to hide when the market is going against you as quickly as possible but, you better come out when the markets are going in your favor and don't just sit on it and say, "Well yeah, I'm making money, this is great." If the trend is in my favor, then, every day I am looking how to make more and how to press it further. That's really my style: explicitly aggressive when I have the best of it and then trying to be much more cautious and hide when things are going against me, cutting losses quickly.

Matthias Knab: Neal, you got some massive press about your 2022 returns in your Contrarian Macro fund. What do you think would be a reasonable performance looking into 2023?

Neal Berger: Well, any reasonable performance above zero is great. I'm making money or I'm losing money, that's the way I look at it. Obviously, risk-free is a little bit higher today than it was in years past, so, if I'm outperforming risk-free, then I'm doing a decent job. Obviously, my expectation and hopes are higher, but I don't look at performance metrics in a certain way. Rather, I'm going to take as much as the market gives. If it's a very lucrative environment like 2022 where both stocks and bonds go down, and every thesis that I have plays out correctly - we'll have some volatility of course, we may be able to make a tremendous amount of money and vice versa.

We'll see if markets play out this year with a similar type of opportunity set. If it does, I'll try to capitalize on it as much as possible without looking at any specific target. If I make 300%, that's great. If I make 20%, that's also great. What's not great is being on the losing side. It's, unfortunately, part of the business that we may have to accept some losses every now and then, but we're trying to minimize that. The positive side of the ledger takes care of itself if you focus on not losing too much money. The positive side of the ledger will be predicated on the opportunity set in the market, and obviously, nobody can figure that out today. Still, I think there's no reason to say that the trend has changed or that the environment has changed. Typically, when you have markets on the move like we do today, they tend to go for several years.

This makes me think that we probably have a very fertile environment going for the thesis that I have, which is really rooted in fundamentals, the reversal of the $25 trillion of stimulus that had been injected into the system over the past dozen years or so, first in response to the global financial crisis and then more recently in response to the global pandemic that we had. The first collateral effect of that was massive asset price inflation. Having the global economy screech to a halt in response to COVID, and stock markets going up like a rocket ship, isn't a normal condition in any universe. Rather, it's just an abnormal, counterintuitive, artificially engineered market environment.

Having $19 trillion of sovereign debt trading at negative nominal interest rates is just not rational, normal, or appropriate in any universe. But, looking back on it, it happened, it's factual, so I think we all must observe such phenomena with a lens that says these things happen, why did they happen, and what will be the consequences eventually? My strong belief why they happened is that when global central banks are injecting an ocean of liquidity into the system to the tune of $25 trillion, you're just going to have markets do what they did, you're going to have massive asset price inflation.

And so now that we're hopefully beyond the peak COVID intensity and years have passed since the global financial crisis, the central banks must normalize what was always to be considered a temporary situation. They must normalize their balance sheets and therefore change their posture towards liquidity by 180 degrees, going from a liquidity infusion posture to liquidity extraction. This will provide a headwind against all asset prices and all asset classes the same way it provided a massive tailwind to support the direction of all asset prices previously.

This asset inflation didn't just happen in the global stock and bond markets, we also saw the proliferation of 18,500 cryptocurrencies and NFTs, price explosion of rare watches, SPACs, and private equity valuations. Everything that could go up was going up, as everything was impacted by the massive influx of capital into the system. And now, central bank balance sheets are normalizing, and liquidity is starting to come out of the system, what was a tailwind has now become a headwind.

That's the fundamental thesis behind the fund. The central banks have an urgency to do this because we are seeing a secondary collateral effect to the massive infusion of liquidity, which is consumer price inflation around the world. One could argue whether it's 5%, 6%, 7%, or more. It doesn't really matter all that much what the number is exactly, it just matters that for the first time in 40 years, we're seeing a unicorn. Most of us have never actually traded or invested through an inflationary period. You've always heard about inflation, but we've never actually seen it. So, in that regard, it's somewhat of a unicorn. Does this thing really exist? But now we are seeing and feeling it, and the central banks, to their credit, are responding very aggressively and seriously to it because you don't want it to take root and grow and get out of hand like it did let's say in the 1970s where we had 20% interest rates.

Therefore, central banks are getting ahead of it in an aggressive way. They are attempting to normalize their balance sheets, but this is a long-term process, it's not going to happen overnight. They are tightening, interest rates obviously are continuing to go up and those are the conditions that are providing a headwind against asset prices. This is really my fundamental thesis combined with the price action because, for me, theory is not valuable unless it's combined with the price action. The price action is the bible. And what we see here is that markets are in longer term downtrends across all assets whether you're looking at stocks, bonds, or cryptocurrencies. Whatever you happen to be looking at even, the price of rare watches, any of these asset classes are all heading downward over the time frame that I'm speaking about, roughly the past year or so.

When a fundamental thesis and the market price action are coinciding with each other, that's the opportunity set when a macro guy like me really should be playing aggressively. That's what we did during 2022 and that's what we're going to continue to do during 2023 until the market suggests otherwise. When the price action changes, obviously I must change my posture, become less aggressive, and/or change direction, but there's nothing that I can see on the horizon that would indicate this at this moment, although I'm watching vigilantly every day.

Matthias Knab: It's obviously difficult to pinpoint how long the current downtrend will last, and how long will we see these consequences of central banks reversing and taking liquidity out. I recall from our previous conversations that you tend to think that this might be a multi-year process, which would translate to a multi-year fertile environment for your contrarian macro strategy, no?

Neal Berger: I don't have a crystal ball more than anyone else. On the other hand, I guess having been in the markets as a trader for 33 years, I tend to have observed that things take time to play out. The bull market that we had lasted since 2009. So, after 12 or 13 years of a bull market, I think it would be incredibly nave or dare I say arrogant of me or anybody else to suggest we're done with this downtrend, just like it was arrogant to step in front of the bull market when it was running and say, well, the bull market is going to stop here when there is no evidence to support that. Typically, these things take a while to play through the system. The Fed just announced last year that they are allowing $85 billion a month of fixed income securities to roll off their balance sheet starting in September 2022. That was only a few months ago.

Lagarde announced at the last press conference that the ECB is going to allow 15 billion euros roll off starting in March, so that's upcoming. That is why I tend to think that we are just in the beginning stages of this balance sheet normalization process and that it will take some time to filter through this to the system, but, like I said, I am also vigilant and keep checking the price action regularly.

Again, the price action is the bible, the rest is just conversation. If the market is continuing in the downtrend, then I have to continue to play it as a downtrend and if things change in that regard, irrespective of what I may think fundamentally, I have to adjust myself and I need to respect the market price action above all else.

Matthias, it's not only you, literally everybody asks me: When is this going to end? What's the price target? But, except for hindsight, there is no such thing as a price target or when it's going to end. It could have ended last week or maybe it will end 10 years from now. I have no idea and neither does anybody else. The answer to that is you've got to watch the price when the market stops being on a 45-degree angle to the downside when you pull out a daily bar chart of the S&P and it starts to go sideways or dare I say, starts to be more of a 45-degree angle to the upside. When we see this type of action, then I'll know that I must change my posture, and everybody else will know as well for themselves. But until that happens, I'm not looking to make price targets and arbitrary guesses as to when or at which price it's going to stop. Nobody knows. We could go down to a thousand points on the S&P or this could be the bottom. It's a futile exercise to try to make those kinds of guesses either in terms of time frame or price target.

Matthias Knab: Let's look at your firm, Eagle's View Capital Management and you as an investor in hedge funds. You have been an investor in hedge funds for over 25 years on behalf of high-net-worth individuals, family offices, select institutions, et cetera. In that role as an allocator to hedge funds, what would you say is your edge?

Neal Berger: Well, I feel that I have quite a bit of experience doing this. I think my sourcing capabilities in terms of relationships to find undiscovered and unknown managers and funds is also a big edge. Most allocators that I've met do not come from the kind of background that I come from. Hardly anyone has an actual trading practitioner's background. So when I'm looking at a manager, I'm able to put myself on the same side of the table as that manager. We do invest in a lot of trading-oriented strategies even if they are not necessarily macro. I can talk the language of the manager that I'm speaking with because I'm a practitioner myself.

What I am going to explain now is, I believe, very important to understand how we pick and invest in hedge funds at Eagle's View. First, I think I've developed a good sense of what is an edge and what isn't an edge, and that has evolved over many years. What I am doing specifically here is looking for positive expectancy. Positive expectancy is a mathematical term defined as a greater than 50% likelihood of winning. It's the same thesis that casino owners operate on. When you are providing a blackjack table, craps table, or slot machine, you have positive expectancy and the player has negative expectancy, meaning you have a greater than 50% chance of winning on every roll of the dice, on every turn of the card, on every pull of the machine.

In the same way, we are looking for positive expectancy, and in order to have positive expectancy, you need to have some sort of an edge. When I'm talking to managers, I want to know exactly what is it that gives them positive expectancy, what it is that gives them an edge, just like the question you asked me.

Of course, the definition of an edge is not static. Assets in hedge funds have grown from maybe 50 billion when I started in the industry to over 4 trillion now, so the industry is saturated with a tremendous amount of capital and a tremendous amount of people looking to find inefficiency and positive expectancy.

In the early 1990s, somebody might have told me, "Well, I graduated top of my class out of Harvard, I work 17 hours a day, I speak to management, I speak to the customers, I speak to supply chain." That might have been an edge 30 years ago, but today, with all the algorithms in the market, all the quants, and all the geniuses, that's no longer enough of an edge to achieve positive expectancy in my opinion. We also tend to like niche strategies. Electricity trading is one example. In that space, you have 3,300 different utility companies that are buying and selling power 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year to satisfy the needs of their constituents who need to put on their lights, heating, and air conditioning.

Those utility companies in the market are non-profit motivated. They are trading power for supply management. So, in electricity trading and all other strategies, I'm always thinking about, "What is the edge? Who's providing the edge? Why are they providing the edge? How long do I expect the inefficiency or the edge to persist?" And the demand-supply equation between the edge providers and the edge takers. The edge provider may be the utility companies, or maybe it's an international corporation that's looking to hedge its shipping costs because they're doing deals a year from now, so they are willing to pay away inefficiency because they want to lock a certain price in and have a match between their assets and their liabilities. I'm always looking for that demand-supply equation between the edge providers, who are providing the juice to capitalize upon, and the edge demanders, which could be very sophisticated hedge funds that are trying to capture the inefficiency that's being provided.

Cryptos are a good example. There was a time, say five years ago or so, when there was a tremendous amount of retail participation during the massive bull market in Cryptos, and many speculators were trading, buying and selling, in a very inefficient manner. So, on the one side, you had lots of retail customers who, in a very dislocated way, were trading all over the world, and you had very few hedge funds that were involved in this. Even the old-fashioned arbitrage where you could buy on an exchange at one price and sell on another exchange at a higher price simultaneously was working. That was the quintessential example of an arbitrage back in the 70s maybe, where you could buy gold in Chicago at one price and sell it in New York at a higher price and vice versa, for one reason or another.

Matthias Knab: So, obviously you find more of that edge in niche and capacity constrained strategies, right?

Neal Berger: That is correct, I tend to look at more niche-oriented and more capacity constrained strategies. I don't do this to be fancy, but because they are uninvestable for the biggest investors in the hedge fund industry. This creates a situation whereby the edge demanders are reduced in those strategies. When you look at where that $4 trillion of assets comes from, it's mostly from the largest institutions in the world: sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, university endowments, large family offices. Those guys are so big that making a $25 million allocation or $50 million allocation, for the most part, doesn't move the needle for them. And so, they have to look at making allocations in the hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars in order to move the needle. So, there's only a certain subset of strategies within the hedge fund universe that those investors can invest into, whether it's long/short equity or credit, or some form of macro or CTAs. They really can't get involved in the more niche, more capacity constrained strategies because the capacity available to them is not meaningful.

I seek environments that don't have as much competition as some others. I'm looking to play in the softest playing field. I'm looking to play at the poker table where the least experienced players are playing, and the least amount of professional poker players are playing. I like to fish in a pond with the least number of fishermen. I tend to gravitate towards these more niche oriented, capacity constrained strategies because the amount of money that's trying to capitalize on whatever edge is available is just less than it is in some of the larger and more mainstream strategies.

Matthias Knab: You mentioned how assets have ballooned in hedge funds, from $50 billion when you started to now over $4 trillion. With that, another development we saw is the rise of passively managed funds which has risen to over 45% in 2020, up from 44% the year before. What is your view on the rise of passive investing? Is it creating even more fertile ground for you and your niche strategies, or is this something you worry about?

Neal Berger: First of all, I think you're talking about stocks, right?

Matthias Knab: Correct.

Neal Berger: When I look at the world of hedge fund investing, equities are only one sleeve of the possible universe of strategies that I can deploy. I can be involved in electricity trading, or in natural gas basis trading. I can be involved in all kinds of markets, even cheddar cheese. To me, there's nothing so special about equities in the quest for edge and for positive expectancy. But to answer your question, it changes the inefficiencies.

30 years ago, more actively managed mutual funds dominated the scene. The Fidelity Magellan's of the world, dating back to Peter Lynch and later Jeff Vinik, were stock pickers and they tended to pick individual names which in turn created big opportunities for strategies like statistical arbitrage. Just to use an example, if Fidelity Magellan is buying Coca Cola, their size was pushing Coca Cola stock out of line with its industry group, or a corresponding pair, say, Pepsi Cola, because there was a short-term demand-supply imbalance. And so, at that time, statistical arbitrage was able to capitalize as a liquidity provider, because they were the edge providers. The slippage generated by large mutual funds getting in and out of different individual names was creating inefficiency for statistical arbitrageurs to capitalize on, which is sort of what I was talking about before.

As a consequence of moving more toward passive indexation, today, we have different types of strategies, for example, index rebalancing, where certain names are coming in and out of indices whereby funds that track indices now need to buy, depending on the particular index that they are tracking. They also need to sell other stocks that are falling out of the index that they track. That forced buying and selling creates opportunity for arbitrageurs to provide liquidity to those participants that are buying and selling those names because the players who track an index simply have no choice because that's what their mandate is, they have to own a certain number of stocks in a particular index. As more money flows into the index, those passive managers need to continue to buy those stocks that are in that index, and they need to sell stocks that are coming out of the index.

I like to say that I am not in the prediction business, I'm in the observation business. Part of being in the observation business is observing the way the world is changing. We have indeed gone from more active investing via say more actively traded mutual funds to more index-oriented products. But, in the end, it's just a different way of trading, and different edges and inefficiencies are generated as a result of this changing environment that I'm observing. I then try to take advantage of this in my investing behavior.

Matthias Knab: Now that you are the "163% man", are people becoming interested in you as a person, trying to understand what shaped you and where you are coming from?

Neal Berger: While I don't confirm specific returns publicly, I'm getting a ton of emails following the recent global media coverage. Many young people are also writing me asking, "Could you tell me how you started," and that sort of thing. Of course, many are looking for jobs.

So, I am glad I had the opportunity to cover some of this with you today, Matthias. You could say that I've got a story that's never been told before. I'm not sure if it's the most interesting story in the world, but it's a story that's never been told, so thank you for this opportunity.

There is indeed a huge audience that is interested to know the evolution of how someone gets to the seat where I'm sitting. And that evolution is different for everybody, right? Any one of my peers will have their own interesting story of how they ended up in this seat.

While we've received a lot of media attention recently related to our Contrarian Macro Fund, I think the equally interesting story here is the multi-manager strategy we've been running at Eagle's View since 2005. For sure, it's fantastic that many people know me now and want to talk to me because of our Contrarian Macro Fund. But Eagle's View as an organization has achieved what we've sought to achieve for investors across all our products, that, to me is the big story. Our pure absolute return vehicles are one of a kind, in my opinion. They don't grab the major headlines, because we're not making triple digit returns, and for sure, everybody loves headlines with huge performance numbers. However, the fact that Eagle's View's multi-Manager Funds have been able to provide investors with a way to seek returns with near zero beta throughout so many different types of market environments is something my team and I are incredibly proud of. We feel that our products have been successful in achieving their mandates. I think that story, that ability to have been successful over the course of the history of our organization and as well as within our advisory business is rather outstanding.

Mainstream markets can have huge moves; however, I'd like to think that our investors have this peace of mind that Eagle's View's multi-Manager offerings are just not exposed to these overall direction moves in a systemic manner. If the stock market crashes or we have a month like March of 2020, or other chaotic market environments, we believe investors in our flagship absolute return offerings have historically enjoyed a great peace of mind that maybe we'll lose a little bit, maybe we'll make a little bit, but at the end of the day, Eagles View's multi-manager fund is just not really going to be impacted much one way or another. And that's because of our strategy diversification, we do not believe we are exposed to any single exogenous factor that could really cause an enormous downturn.

If you can generate respectable pure absolute returns, without correlation to the stock market, to the bond market, to commodities, with low drawdowns and low stress, that's highly attractive and a story worth telling.

So, in my personal investing preferences, I would give that kind of product a lot of consideration as a long-term investment. Of course, huge returns are great. However, at the end of the day, we're betting on major market moves here in the Contrarian fund, and it's not without volatility, and not without risk. If the markets go against us, we're going to lose some money. We are going to try to minimize those losses, of course, but at the end of the day, we are taking a stand and making a bet on a particular thesis and a theme, and that theme could be right, or it could be wrong. We think it's right, and we'll try to mitigate any negative effects of being wrong, meaning losses, but, time will tell.

The nice thing about our multi-manager products is that we're not betting on any specific thesis. Markets go up, markets go down, I feel confident we're going to be up by the end of 2023. I hope I'm right.

We try to operate the multi-Manager business much like a casino owner. A casino owner doesn't worry too much about whether they are going to make money on the gaming side of the business because they know the house has an edge and positive expectancy. If we are correct that we have positive expectancy and an edge, we can have that same comfort that over a statistically relevant sample size of data and observations, we're going to come out winning. I don't believe Steve Wynn is checking his gaming P&L every day. Although I don't know the man personally, I imagine he's not asking, "how did we do in craps today or how did we do in the slot games or how did we do in blackjack?" as he's got a mature business and understands that he's got an edge versus the players. If he is asking those questions, I believe it's out of curiosity, and to ensure that things are running smoothly, there are no anomalies that may indicate cheating or he's just a p/l junkie like many of us. More likely, he's confident that they have positive expectancy and that over any statistically relevant sample size of timeframe, they are going to be winning on the gaming side because the house has an edge. I feel the same way. Steve Wynn's concerns are bringing enough people in the door, having people come to his casino versus other casinos, and having an honest game with no theft and cheating, but I doubt he's overly worried about the losses on the gaming side because he knows that the house has the edge over a reasonable sample size of bets.

That's how I feel about our multi-manager products. I don't really worry too much and don't lose sleep because I believe strongly that we have a highly diversified series of positive expectancy investments. We are highly diversified across many different types of strategies. The beauty of this diversification is that even in the context of having positive expectancy, some of our strategies may suffer large down months and large down periods, but an investor has not historically been impacted looking at our return stream because there is going to be the whole mosaic of some managers underperforming their expectancy and other managers outperforming their expectancy, with the majority performing in line with their longer-term expectancy. That's, by the way, the same model, approach, and philosophy the large multi-strategy funds are all using in my opinion. They are all attempting to put together a highly diversified series of positive expectancy investments that are both internally uncorrelated to each other and externally uncorrelated to the broader markets with an overlay of strong risk management. That's why you're seeing this sort of smooth and steady performance throughout any type of market environment generated by the multi-strategy hedge funds, which we attempt to duplicate within our multi-manager product.

Global macro trading and investing is very environmentally dependent. When there's a big opportunity set, you make a tremendous amount of money, and you try to capitalize on it as much as you can. There are not always these tremendous opportunity sets. In my opinion, we happen to be in the midst of one right now, which it was I started the Contrarian Macro Fund. But it's not necessarily a product that is always for all seasons. It's a product that has its environments. The multi-manager business operates on the theory that there's always an edge somewhere and that's a great long-term business and investment opportunity in my view.

Macro investing has certain more difficult and less attractive periods, which is why I took a pause from macro trading during the time when the central banks were heavily influencing markets and macro trading was more difficult.

Matthias Knab: Maybe you weren't actively trading a macro fund before you launched this one in 2021, but you always expressed your views and were constantly investing through your fund of funds and multi-manager portfolios, no?

Neal Berger: Correct. There was an extended period where I wasn't actively involved trading traditional macro products, rather, I was expressing my skills as a portfolio manager utilizing a different palette. That palette happened to be non-correlated hedge funds instead of stocks, bonds, and the dollar. In effect, I was and remain a portfolio manager of hedge fund securities within our multi-manager offerings.

At the time I started the macro fund, I felt I had a good handle on the environment, what had happened in markets, and what was going to happen. From that perspective, just launching the macro fund was itself a good macro call, right? We will see if I make the same good macro call when the environment is not as attractive to shut down the macro fund. For sure there will also come a time when macro is just not as fertile as it is today, but right now, this happens to be the season for it, and I am planning to take full advantage of it.

On the other side, the multi-manager fund is a fund that I hope to be running for the rest of my life to my dying day. I believe that there's always going to be edge, always some inefficiencies in the market that can give you positive expectancy. Many of my macro peers have also done well during 2022 and I take nothing away from them, in fact, they deserve tremendous credit. They have been running global macro funds for long periods of time and had to fight some challenging market conditions during that time. I stood aside from macro for a while running our multi-manager funds and trading in hedge funds only.

But, as you said, I was still trading but used a different palette to express that skill. Instead of trading the S&P or trading the bund, I chose to trade hedge funds, right? So, you could call it portfolio management, because it connotes a little bit of a longer-term timeframe. When I invest in a hedge fund, the way I look at it is, essentially, I'm buying that position, right? Just like any trader or any portfolio manager. When I choose to redeem from a hedge fund, I'm selling that position. So, all the while and continuously, I've been investing in hedge funds, I've been engaging in portfolio management of hedge fund securities.

We invest in a variety of hedge funds, and I'm regularly investing in new ones or redeeming from certain existing ones as inefficiencies dissipate or for other reasons. Ideally, I never have to redeem from a manager, though, that is unrealistic. As the world changes, so does the opportunity set for inefficiencies and positive expectancy.

|